Jervis Johnson - English version

ENTREVISTAS

To speak of Jervis Johnson is to refer to one of the leading figures and a true benchmark in the history of Games Workshop. The extensive list of games he has designed throughout his career, along with the numerous publications he has contributed to, make addressing his entire journey in a single interview a titanic task.

Therefore, with this blog's focus being primarily on dungeon-crawler games, our discussion will focus on that influential genre, while also touching upon other classic titles from a golden era of board game design. I am incredibly grateful that Jervis has taken the time to share his memories and insights with all of us

I would like to thank HispaZargon for his collaboration in the making of the questions, and specially to Tim Evans from Filmdeg Miniatures for facilitating this interview.

Full interview with Jervis Johnson

To kick off this interview, I won’t ask you to name your favorite game from all those you’ve designed. Instead, what do you believe are the essential qualities that make a game truly good? Is there an element you consider indispensable?

Jervis Johnson: This is a hard question to answer succinctly. I guess I would say that for a game to be good the designer must have a clear idea of what they want to achieve, and then they must attain those goals with the minimum amount of rules overhead. This is not to say that a good game needs to be simple; if you want to design a game that is (say) a simulation of the entire war in the Pacific in WW2, then it will be necessity be a complex game. The trick is to know what you want to achieve first and then design a game that does that as straight-forwardly as possible. (As an aside, the example I used for the WW2 game is based on a favourite game of mine called Pacific War that has two huge maps and over 2,000 playing pieces! That doesn’t stop it from being an awesome game.)

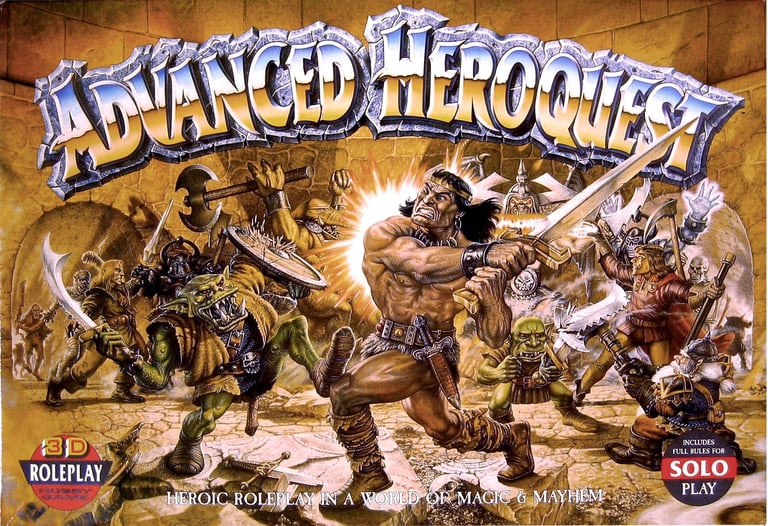

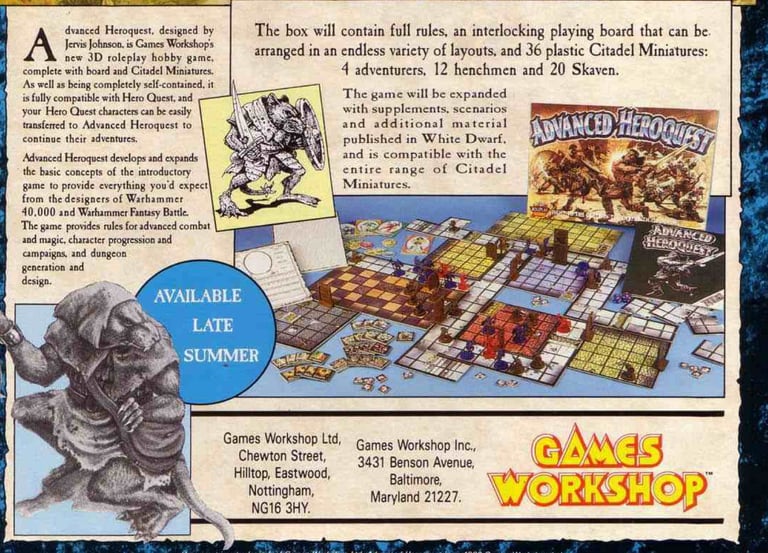

The idea of a dungeon crawler with miniatures and a role-playing-style board, like Advanced Heroquest (AHQ), was it already in mind to be produced in the offices of Games Workshop (GW) before the design of HeroQuest (HQ) by Milton Bradley (MB) began? I have read conflicting information about the agreement Bryan Ansell reached with MB, but I am not sure where the concept for this game was originally conceived, whether at MB or GW.

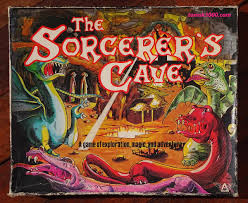

JJ: I don’t know if GW or MB came up with the idea for Heroquest first. Games a bit like this did already exist (Sorcerer’s Cave is a good example) so I think something like it was that was probably discussed at both GW and MB before the concept for Heroquest was landed on.

In 1995, GW released Warhammer Quest (which was the natural successor to Advanced HeroQuest). Why do you think they opted for that title for the game instead of continuing with the Advanced HeroQuest title?

JJ: By the time that WHQ came up Games Workshop was established as a successful business, and the Warhammer brand was firmly established. In short, GW no longer needed or wanted to ride on the coattails of a company like Hasbro/MB – we could get the success we needed without their help or needing to share the glory.

Stephen Baker, creator of HeroQuest by MB, told me in another interview that several people from GW participated in the design of the MB game, both in terms of the artistic aspect and the fantasy world's setting, as well as in rule design and playtesting. Some of the people he mentioned were Rick Priestley, Phil Gallagher, and yourself. Could you please share some details about what your involvement with MB entailed? What were the playtests like?

JJ: Unfortunately, I only have very hazy memories of playtesting Heroquest. In my defence this was a busy time at GW and the development of Heroquest was not something I was directly involved with. As far as I can recall it was well-developed when I became involved and there was little if anything I was able to add to it other than saying it was a great game.

AHQ includes a specific section with rules for playing with the board, furniture, magical items, and heroes from HQ, which I believe was an excellent addition and one that fans of both games greatly appreciate. Did anyone from MB participate in creating this section of the AHQ rules, or was it entirely the work of the GW team?

JJ: I can’t recall anybody from MB being involved in the process.

At some point, I heard that you worked with Albie Fiore to develop AHQ. What role did Alby have in the development team?

JJ: No, Albie had left GW long before we started work on AHQ. However, Albie was a hugely talented person and one of the best Dungeons&Dragons GMs I ever played with. I was incredibly lucky and was able to play in a long running D&D campaign with Albie, which was one of the formative experiences of my life. So, when I was asked to create AHQ, I tried as much as possible to channel as much of Albie into the game as I possible could. This means that although Albie wasn’t directly involved, he was hugely influential on how AHQ turned out.

The puzzle-tile system for discovering the dungeon in AHQ was quite unique for its time, similar to the one used in Space Hulk around the same period. Was adopting this tile system a decision made before or after the first edition of Space Hulk was developed? Additionally, was there ever any consideration of using a fixed board in AHQ, more like the traditional board games?

JJ: I can’t remember which out of AHQ or Space Hulk was the first to use map tiles. They both came out at roughly the same time and I worked on both, so I would think that the ideas were developed in tandem. Hower the idea of using map tiles, especially for a dungeon crawl wasn’t unique at the time. Games like the Sorcerer’s Cave used a tile-laying system, as did Death Maze by SPI, and I’m sure there were others as well. Just as important were the ‘Dungeon Floor Plans’ that GW produced for use in D&D; they are little remembered today, but when I joined GW in the early eighties, they were one of our best-selling products. So, all in all, using tiles in this was a well-established idea, and I can’t remember us ever considering using a fixed map instead.

Do you remember who was part of the AHQ testing team? I’ve always been curious about how testing teams were organized at GW; were there multiple teams that later exchanged feedback? Any essential advice that you can give for conducting good playtests?

JJ: I can’t remember who exactly was on the AHQ team. There were only a few designers/developers working in the Studio, and we all tended to have a project we were working on ourselves and would all help each other out with playtesting. However, deadlines were incredibly tight back then, and very, very little time was included for playtesting. We often wrote material, played a game or two with the rules, and then the game would be off to the printers and we’d start on the next title. It’s something of a miracle the games work as well as they do. So, in short, AHQ was definitely not well playtested!

Over the years the importance of playtesting has become more generally accepted at GW – though it’s still hard to make managers understand that ‘just sitting around playing games’ is an important part of the design process. Good playtesting requires that you get as many games in as possible, but that you also learn to filter out feedback that would guide the game away from the core design principles you have established for it.

AHQ had a greater depth of rules and setting compared to other dungeon crawlers of its time, offering players a far richer, more tactical experience that felt closer to role-playing games than to traditional board games. Today, AHQ is considered a cult classic and commands high prices on the second-hand market. However, do you believe it achieved sufficient success in its day? Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, is there anything you would change regarding its rules or overall design?

JJ: I can’t say I’ve ever thought seriously about the success AHQ achieved or what I’d do to improve it. It did perfectly well at the time, which was good enough for me, and in any case I would have moved on to whatever project I was assigned to next. One of the difference between AHQ and most other games that I’ve worked on is that it had only a very limited ‘tail’ of products and expansions; it’s purpose was that GW had a game of its own that was linked to Heroquest, to act as a bridge for players that bought games in toy stores and introduced them to the GW hobby. This meant that I never really got the chance to think about doing a 2nd edition or what I would change if I did. In a way that it is a good thing – AHQ has remained its own thing, with its own quirky style, and there is nothing wrong with that.

The magazine White Dwarf (WD) featured several articles and adventures for AHQ. Did you participate in any of those publications? Do you know the main reason why support for the game was discontinued?

JJ: I can’t remember having anything to do with WD support for AHQ after it was launched. However, I may have written a support article as part of the process of designing the game and not remember it. I don’t know exactly why AHQ was discontinued, but I would think it would mainly be because it had served its purpose as a bridge into the GW hobby and it was felt that it was no longer needed. I don’t think that AHQ was ever seen as something that would be in the GW range for a long period of time.

Regarding the miniatures in AHQ, do you recall who decided the content of the base game? I ask this because most fans bought the game for the box art created by John Sibbick, where you can see the barbarian and almost all the monsters from HQ, while inside the box, there were only Skaven and mercenaries. (I’m sorry to say it, but I believe that disappointed more than one buyer... including myself!)

JJ: Sorry, I can’t help with this question. I wasn’t involved with deciding what went in the box or what the box art would be, I just designed the game rules. I think the idea with the box art was to show you could use the models from HQ in AHQ – in other words that AHQ was a sort of expansion for the game – but I can’t say for sure.

Did you participate in the development of the AHQ expansion Terror in the Dark? Unfortunately, it was only published in English, but do you know if there were plans to release it in other countries? (In Spain, we know it was going to be released with the title Las Tinieblas del Horror) Was there any intention to launch more expansions for AHQ? (*) I have asked Jervis if there was any material that was cut from AHQ, and as far as he recalls, everything he produced was included in the final game.

JJ: As far as I can remember I was not involved on the Terror in the Dark expansion, and I don’t know if there were ever any plans to publish it in other countries. I don’t think there were ever any solid plans to publish further expansions for the game.

Nowadays, it is undeniable that Space Hulk is one of the most influential and remembered games in GW’s history, and you were one of the architects of its success from the very beginning. Much has been said about Space Hulk and what it meant, so we won’t delve too deeply into it now, but I can’t help but ask: do you agree with removing the real-time clock in the second edition of the game?

JJ: As one of the people responsible for removing the time clock in the second edition of the game, I can say without hesitation that it was a foolish and misguided idea. However, you live and learn, and so I made sure that the timer was returned in the 3rd edition. 😊

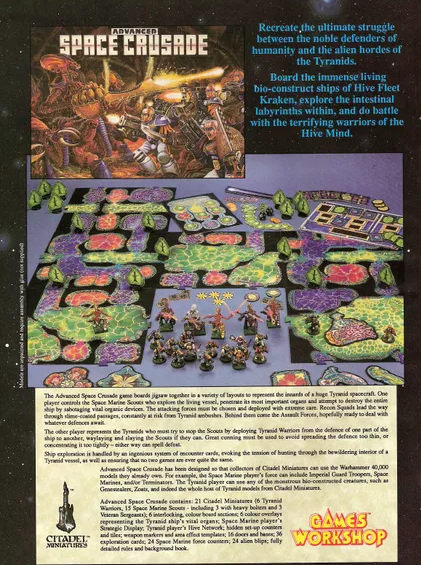

Let’s talk now about Advanced Space Crusade (ASC), a game you also designed in the late '80s... I believe you once mentioned that you are not entirely satisfied with the work you did on that game. Is that true? What would you change about it if you could?

JJ: ASC was far too complicated and intricate for what it was meant to achieve. It was an important game for me because after it came out, I was asked to design a simpler version using the same pieces that was called Tyranid Attack. What I found was that I could achieve much of the same game play with much simpler rules. It changed the way I thought about game design and resulted in the 3rd edition Blood Bowl rules, which is arguably one of the best (if not the best) game I have designed.

Regarding the creation of ASC, it is often assumed that the same development framework was followed as with AHQ and HQ; indeed, once again, there are mentions of SC and rules for its aliens in the GW game’s rulebook. Is it true, then, that ASC was created simultaneously with SC? Did you interact with MB’s development team regarding ASC? (*) I have asked Jervis about Battle Masters and other collaboration projects with MB, and he confirmed that he was not involved in their development.

JJ: As I remember it was designed at about the same time as SC, but I didn’t have any involvement with the SC design team.

Phil Gallagher was one of the main creators of the first edition of the Warhammer Fantasy role-playing game (WFRP). The connections between this game and AHQ are obvious, but to what extent did this role-playing game influence the design of AHQ?

JJ: Speaking personally, it didn’t influence me very much. The biggest influence on AHQ was Albie’s games that were played with the 1st edition Advanced D&D rules by Gary Gygax.

In the late '80s and early '90s, GW released many smaller-format games, such as Ultra Marines by Andy Jones, but given its similarities to other games you had previously worked on, like Space Hulk or ASC, did you collaborate with him on the design of Ultra Marines, as you did with the game Space Fleet? Can you tell us a bit about why GW bet on these smaller formats and how it was decided who would design each one of them?

JJ: I don’t recall working directly with Andy on Ultra Marines, though I’m sure we chatted about it. Andy was in charge of the small format games and decided along with Rick Priestely who would design each one, though it would depend primarily on who had enough free time to design the game. The purpose of the games was to act in a similar way to HQ and SC – games that could be sold in toy stores and act as a gateway to the Games Workshop hobby.

In fact, there are three games designed by you and published during that same era that are not very well-remembered today but have always received good reviews: Battle for Armageddon, Doom of the Eldar, and Horus Heresy. Like Space Fleet, none of these games required miniatures to play, which somewhat broke GW’s and Citadel usual commercial rules. How were these types of games launched onto the market?

JJ: The games came about because Bryan Ansell was interested in seeing if we could create our own version of the board wargame hobby, with games like those produced by Avalon Hill, SPI and (later) GMT, but tied to our own IP. So, they were an experiment really, which I became involved with because Bryan knew I like playing Avalon Hill and SPI games. It didn’t quite work out, and although the games did okay, they didn’t really set the world on fire, and so the idea was quietly dropped. I had fun working on them though.

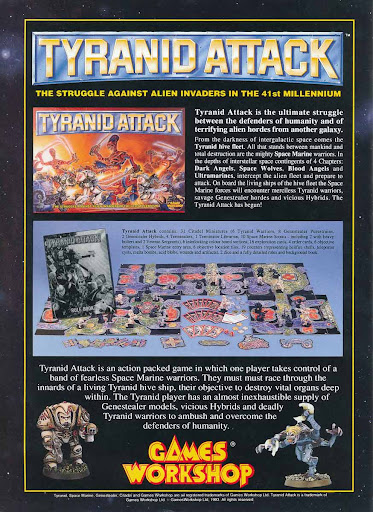

During those years, GW also published Tyranid Attack, another game you designed. There are several aspects of the game that are highly regarded, such as its very straightforward rules and the inclusion of exploration cards, as well as the addition of numerous Space Hulk miniatures. However, do you think we can say that Tyranid Attack is a simplification of ASC, or was something different intended from the start? What motivated the launch of this game, and how was the process? And I can’t resist asking... why weren’t doors included, as in ASC?

JJ: I’ve already covered this a bit earlier on. Tyranid Attack was something of a side project, designed to be a simpler more accessible version of ASC, and (as I remember) to help us clear some excess stock of the board tiles we had left in our warehouse. I don’t know for sure, but I would think that the doors weren’t included because we didn’t have any left-over doors in our inventory!

And to conclude the interview, I would also like to ask you about Talisman. This game was, even before the arrival of Space Hulk, one of GW’s flagship products in the market. It evokes nostalgia and memories for many players, but the most highly regarded edition of Talisman to date is the Third Edition (precisely the one you designed). I understand that much of the credit for its success belongs to the original idea’s creator, Robert Harris, but in your opinion, what makes the third edition of Talisman so special?

JJ: Thank you for the compliments, but the success of Talisman is all down to the original design of the game and therefore the credit is Robert’s; all I did was try to make sure that the wording of the rules and cards was tighter and more precise, and that the end game was quicker. As to why the 3rd edition was a success, I think this probably comes down to it having a good initial game brief. I think this was cooked up by Rick Priestely and Tom Kirby, and it gave me a really good idea of how the game and all of the expansions were meant to work and what we were looking to achieve. As I mentioned right at the start, having a clear set of design goals (and then sticking to them) is a key element in making a good game, and that was what I had with 3rd edition Talisman.

I want to extend my sincerest thanks to Jervis Johnson for his time and for the candidness with which he answered all the questions. Hearing first-hand about the design philosophies that shaped the hobby, has been invaluable.

It was a pleasure to learn more about this formative era from someone so influential, and I am deeply grateful he took the time to share his experiences and creative process with all the readers.