Rick Priestley - English version

ENTREVISTAS

For many, the name Rick Priestley is synonymous with the golden age of tabletop wargaming. As one of the foundational figures at Games Workshop, he was the chief creative force behind two of the most influential wargames ever published: Warhammer Fantasy Battle and Warhammer 40,000. His work not only shaped the lore and mechanics of these worlds but also defined an entire generation's approach to the hobby.

In this interview, we had the pleasure of sitting down with Rick to explore his time at Games Workshop during the 80s and 90s, delving into the creative processes, collaborations, and philosophies that guided his legendary designs.

Thanks to HispaZargon and Albertutxo for helping with the questions for this interview. A special thanks to Jervis Johnson for facilitating this interview.

Complete interview with Rick Priestley

The Genesis of a Hobby

First off, thank you so much for joining us! We're all huge fans and would love to hear what you're up to these days. Have you officially retired from game development, or are there any exciting new projects you're currently working on that you can share with us?

Rick Priestley: I don’t know if it’s possible to retire from games development – any more than you can retire from the gaming hobby. If these things bite you, they never let go! Designing games has always been something I’ve done as part of the hobby, even before I worked for Games Workshop. When I was at Games Workshop there was only a very brief period when I was purely a ‘games designer’. I had many different jobs whilst I was there – including a stint at running the studio in the 90s.

Any projects I take on these days are usually either for my own enjoyment or to help out one of my compatriots. At the moment, I’m working on a supplement for my spaceship game: Spaceship Battles: A Spacefarers Guide, published by Wombat Wargames and available via Amazon. Apart from that, I add the odd thing to my various collections, most recently I’ve been painting up more ‘old school’ Minifigs for my Persian army. You can read more about that on my Notitia Metallicum blog.

Which of your designs from that era did you enjoy creating the most?

RP: The 80s and 90s? I did quite a bit… well it does cover twenty years! I write (or co-wrote) the first five Warhammers and the first two 40Ks, as well as a bunch of supplements, Necromunda, Mighty Empires, Warhammer Fantasy Role-play: those are all things I think of as ‘my designs’ – although most were obviously team efforts to some extent.

At the time, the thing I would have enjoyed most would have been whatever I was working on. That’s true today just the same as it was then. In retrospect, I do remember the 1992 Warhammer (4th) very fondly, as that was a whole project that would re-base the game and introduce the ‘army book’ concept, which would in turn provide the means of massively expanding the game, the company, and everything that followed.

Could you share a key lesson about game design you learned during your time at Games Workshop (GW) in the '80s and '90s, and how you apply it to your work today?

As it happens, I’ve written a whole book about that very thing. It’s called Tabletop games: A Designer’s and Writer’s Handbook, and it’s published by Pen & Sword, written by myself and John Lambshead.

If I can pick out one thing, it’s always to listen to player feedback and be grateful for it – if folks don’t understand something ask yourself whether you have explained it properly, if they constantly get a procedure wrong perhaps you should change the procedure, and so on. As a comrade of mine used to say, ‘everything tells you something’.

The Milton Bradley Collaborations – HeroQuest and Advanced Heroquest

This blog focuses on dungeon crawler games in general, and HeroQuest (HQ) in particular, so let’s talk about the collaborations between Games Workshop and Milton Bradley (MB).

Was the idea of a dungeon crawler with miniatures and a role-playing-style board, like Advanced Heroquest (AHQ), already being considered at GW before the design of HeroQuest (HQ) by MB began? I have read conflicting information about the agreement Bryan Ansell reached with MB, but I'm not sure where the concept for this game was originally conceived, whether at MB or GW.

RP: I don’t know where the proposal came from. I always assumed that it was Steve Baker’s concept and that he originated the whole thing. Now, the ‘idea’ of taking a dungeon adventure and putting it onto a board format with models, that was pretty much established. In fact, Games Workship make a polystyrene ‘dungeon’ to go with the Fighting Fantasy model range, and a simple set of rules to go with it. And there were plenty of similar things about, including the Dungeon game from TSR – more of a family board game in style but great fun. Drakborgen (Target Games) was a more sophisticated take on the concept for a more hard-core market.

So, I think what made HQ ‘original’ was the way it was packaged as a mainstream (at the time we would say ‘High Steet’) game, and how it was presented as something relatively easy to understand and play without any previous experience of role-playing games. It was unashamedly aimed at youngsters in a way that regular role-playing and hobby games weren’t.

Stephen Baker, the creator of HeroQuest, has previously mentioned that several people from GW participated in the design of the MB game, both in terms of the artistic aspect and the fantasy world's setting, as well as in rule design and playtesting. Some of the people he mentioned were Jervis Johnson, Phil Gallagher, and yourself. Could you tell us a bit about your involvement with MB during the development of HQ? As far as it is known, you were the main contact between the GW and MB design teams, is this correct? Could you please describe how was the design process and who was involved? Were you also involved in the development of AHQ?

RP: I honestly don’t remember having any input into HQ, and I wasn’t part of the team that produced AHQ. It’s entirely possibly that I would have been around when these things were discussed. At that time the main contact between MB and GW would have been either Bryan himself, or the then studio manager Tom Kirby, or possibly one of the project or licensing managers e.g. Paul Cockburn– but not me. Later on, from the early 90’s, I had more to do with the MB side of things because I was running the studio, but up to that point it was not something I was directly involved with.

Advanced Heroquest includes a specific section with rules for playing with the board, furniture, magical items, and heroes from HeroQuest, which I believe was an excellent addition and one that fans of both games greatly appreciate. Did anyone from MB participate in creating this section of the AHQ rules, or was it entirely the work of the GW team?

RP: I don’t know. As I say, I wasn’t involved with the development of AHQ at all.

The box art for Advanced Heroquest by John Sibbick featured a wide range of monsters, leading many fans to expect a similar variety of miniatures inside. However, the box contained only Skaven and mercenaries. We were hoping you might recall who made the decision about the contents of the base game, and if the discrepancy between the art and the models was a conscious choice?

RP: No idea I’m afraid. In those days we were only just getting to grips with plastic model design and manufacture. It was a very laborious process too. So, I would have thought we would have been fairly tightly constrained in terms of box content.

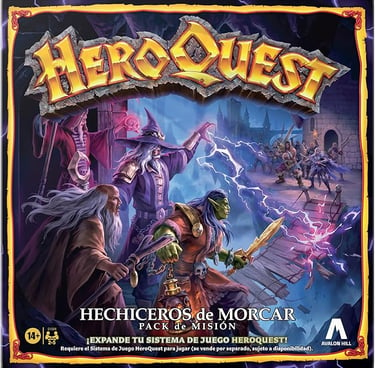

This is a very specific question regarding the main villain in HeroQuest, who is named Morcar. Since HQ is inspired by the Warhammer world from the '80s, do you know if the Morcar from MB has something to do with the Morkar from Warhammer that appeared afterwards? Was there any specific agreement between MB and GW for the lore of HQ to be based on the Warhammer universe?

RP: I wasn’t aware of that. To be honest, it’s a fairly obvious concoction as far as naming a ‘bad guy’ is concerned, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it were a coincidence. Cf Mordred, Mordor, Morgoth. Morcar is actually the name of a Saxon earl who fought against the Normans at the time of the conquest, so it’s an actual historical name.

Speaking of the collaborations with MB, Battle Masters was the final joint release. There are stories of at least two further projects: a chariot-racing game set in the Warhammer Fantasy universe, and a Warhammer 40,000 adaptation of Battle Masters. Do you have any recollections or additional details you can share about these unreleased projects?

RP: Yes, I was fairly closely involved with Battle Masters, the supplementary products for BM and the proposals for follow-up games. I don’t recall anything about a 40K BM – although it’s possible the idea was bandied about. Many ideas get bandied about! I do recall working on a proposal for a chariot racing game, and we may have produced a few mock-ups to illustrate the idea: Elven Chariot, Dwarf Steam Juggernaut, Ork Squiggoth, that kind of thing.

At that time, we were really short of design time for our own projects, and it became increasing impractical to devote a large portion of the designers’ time to making things for MB. Tom Kirby had bought the company from Bryan Ansell, and he was keen to maintain the relationship with MB, but he was also demanding more and more Warhammer and Warhammer 40K models for our own sales teams. In the end, it became obvious we couldn’t do both, and I think the relationship with MB just fizzled out because we needed the designers to work on our own projects.

In 1995, Games Workshop released Warhammer Quest, which many considered the successor to Advanced Heroquest. Did you collaborate with Andy Jones on this project, and if so, could you tell us about your contribution?

RP: By then I was Studio Manager, so I wouldn’t have contributed directly to the project development. I would have proposed and scheduled the project, as I was responsible for the entire release plan at the time, as well as delivering it. I must have written a brief for Andy Jones and then we would have worked out the idea, outlined box contents to a budget, and planned the work. Andy sorted out the design, play testing and so on. I remember playing WQ during development and probably would have kept an eye on the project, but it would have been one of several projects moving through the studio at the time.

I do remember the plastic doorways were a nightmare to produce! We miscalculated the costs on those and had to do a last-minute content revision to bring the game anywhere near budget.

I also remember that the artwork came in – and it was beautiful – but the sales guys got very negative about it and demanded something more colourful. In the studio, we were completely dumbfounded, because we thought the artwork was just perfect. Remember, John Blanche would have steered this through from brief – so it wasn’t a random piece of art in any sense. Anyway, we had to go back to Geoff Taylor, the artist, and get him to rework the picture adding what he described as ‘bolt on colour’. We did take a transparency of the original – I don’t know if that picture ever turns up. Poor Geoff was a bit upset about that – and with some justification, I think!

Warhammer Fantasy Battle (WFB)

What were the primary literary and cultural influences that shaped the first edition of Warhammer Fantasy Battle in 1983? Additionally, which contemporary games had the greatest impact on your work at GW during that period? (For example, RuneQuest, Dungeons & Dragons, or others?)

RP: Gosh that’s a difficult one to answer – I’m tempted to say ‘you had to be there!’.

I suppose one obvious influence has to be D&D because that was so pervasive. Citadel’s main business at the time was selling models for role-playing games, primarily for D&D. The first Warhammer was a skirmish-style wargame designed to encourage our existing customers to play bigger games and to collect entire regiments of troops rather than just the odd one or two ‘role-play’ characters. So, when we put the first Warhammer together, part of the brief was that it had to have rules for all the different models we already made, which were – of course - all the familiar D&D Orcs, Elves, Goblins and so on.

Having said that, we didn’t take anything from D&D apart from those traditional creatures, which were hardly unique to D&D. D&D drew most of its core cast from popular fantasy literature. Many of those books were just common fair to anyone interested in that sort of thing at the time. The Lord of the Rings looms large in any list of fantasy literature, and its tropes, and parodies of those tropes, were probably in the backs of our minds.

The very first Warhammer did include a fairly substantial ‘role-playing’ element. That was just how it was at the time. If you put the words’ role-play’ on a box you could sell it much more easily, the demand for the newfangled role-play craze was insatiable! Once Warhammer got into folks’ hands it quickly became established as a battle game, and we would drop the role-playing elements by the time it came round to doing the next version.

Mechanically, the biggest influence on Warhammer was the game that Richard Halliwell and I wrote before we worked at GW: Reaper. The original version of Reaper was published by the Nottingham Model Soldier Shop; the second edition was published by Tabletop Games. Anyway, when Bryan asked Richard Halliwell to write the manuscript for Warhammer, Richard took our Reaper game system and translated it into D6s, as Bryan stipulated, adding a further step into the combat mechanic to take this into account.

Thinking back to the '80s, could you tell us about the motivations that led to the evolution of a game like WFB from the skirmish fights of WFB 1st edition and 2nd, to the massive battles of WFB 3rd edition and the "Herohammer" of WFB 4th and 5th editions?

RP: Interesting that you should put it like that! What Bryan wanted to do – and what we all wanted to do – was to create a fantasy wargame in the same broad style as other tabletop wargames of the 70s.

Fantasy wargaming took off before D&D existed, mostly using models inspired by The Lord of the Rings (Minifigs in the UK, Der Kriegspielers in the USA) and Robert E Howerd (Minifigs and Garrison in the UK). In the mid-1970s we were already playing fantasy battle games, often using the then current Wargames Research Group Ancient rules with suitable adaptions, or the various rulesets that were often inspired by them, e.g. Leicester Micro-Models Wizards & Warfare.

If you look at my Notitia Metallicum blog, you will find an army of Minifigs ME (Middle Earth) figures that I have re-created using 50 year old models that I’ve collected or bought as re-issues from Miniatures Figurines. That is what we were doing 50 years ago, ten years before Warhammer existed. The games we were playing were essentially battle games with units of figures arranged into formations exactly as classic Warhammer.

There were plenty of other manufacturers in the UK and USA making fantasy models for playing wargames, and plenty of rule sets, all before role-playing took off. For example, Royal Armies of the Hyborean Age (Fantasy Games Unlimited 1975). The Emerald Tablet (1977 Creative Wargames Workshop). SELWG Middle-Earth Wargames Rules (1976 Skytrex). There were many others of varying degrees of popularity, not to mention the countless homebrewed sets, one of which became Reaper!

Bryan’s genius was to recognize that all of these traditional wargames rules were written by and for existing wargamers. They usually started off playing historical games, and their preference was for complex, detailed rules systems, presented in a ‘grown up’ fashion. These were inaccessible if not actually incomprehensible to youngsters, who hadn’t the experience of growing up playing the 1960s rulesets by Donald Featherstone, Charles Grant and Brigadier Peter Young. With the advent of D&D and the popularity of role-playing, there was suddenly a new market for fantasy tabletop wargames, a customer base that was not already mired within the traditional wargames market.

So, the whole Warhammer project – from day 1 – was about re-presenting the tabletop wargaming hobby to a new market with a taste for fantasy stimulated by the sudden and universal craze for role-playing games. The difference between Warhammer and the then current wargames rules was that we adopted the presentational standards associated with role-playing games. I know that sounds mildly ridiculous given how rough and ready everything was. You have to remember, most historical wargames rules were entirely text, usually type-written without illustration or diagrams, more often than not reproduced on a wet copier (such as a Roneo), stapled, and with a coloured card cover if you were lucky. We also chose to explain how the game worked, rather than just present the bald mechanics and expect players to understand what to do, which was usually the case with then extant rulesets. E.g. if you look at a copy of the WRG Ancient rules 3rd edition (the version I started with) you’ll find no explanation of how to play a game. It’s almost impossible to figure it out from the text!

With that in mind, you’ll see that Warhammer didn’t really evolve so much as it adapted to the resources available at the time and the needs of the business. The first version did include role-playing material and the words ‘role-playing’ on the cover. We needed that hook to sell it into shops and to attract the attention of the young prospective players, who might have heard of D&D but would never have encountered a traditional wargame. Once Warhammer became established in its own right – which happened very quickly – we were able to concentrate on building a fantasy wargame, with its bespoke background and supplementary products. In essence, that didn’t change at all throughout the five editions I wrote or beyond.

The main difference between those first five editions is one of resources, The first two were produced by a tiny team (just 2 of us for the first one) with limited resources. By the time we did the 3rd edition the business had grown and we had invested in proper type-setting machinery, process cameras, and many – many – more staff. Bryan thought that the youngsters who had come along at the start of the Warhammer journey would now be older, and would react positively to a more involved game, with a lot more mechanical detail. That steered the game design towards mechanical complexity, which actually worked against it in many ways, making it harder to get into than the previous editions.

The 3rd edition is fondly remembered because it was such a beautiful book, with some fantastic photographs of aspirational games, and incredible production values for the time. And, of course, for many players it was their first taste of Games Workshop. However, by 1992 the business had been sold, Bryan was gone, and we were saddled with the cost of servicing the debt incurred during the buy-out. Hence, we were back to a reduced staff and much-smaller budget, most of which I decided to spend on plastic models. By then, Warhammer was selling very poorly compared to 40K, so it was in need of a relaunch. Hence a slim-lined, faster playing and more accessible version of the game with a more tightly focused model range to go with it.

That 1992 edition became the 4th version and it was updated slightly in 1996 (5th). Although both are often termed ‘herohammer’ the core game is, I think, the best version of Warhammer, and by far the most fun to play. As for the mighty heroes – well it is a fantasy game – and the intent was always that such things should be optional – they were not conceived of as part of the core game itself. I think a lot of the ‘herohammer’ reputation results from our own shop staff pushing the super-powerful characters as must-haves to their young customers. We also introduced campaign packs with that version (5th) in an attempt to revive the narrative style of earlier games – but they never really took off. The players wanted herohammer!

This is more of a technical question, but I am curious about how you designed the magic items for WFB 4th and 5th editions. Did you use any matrix or other system to avoid important imbalances? Could you please elaborate on this matter?

RP: No, we didn’t use a matrix. The general approach was to limit the bonuses within a standard +1/+2/+3 format with the more powerful items having either specific or limited uses, or a degree of randomness. So, the more powerful an item either the less predictable, or the less ubiquitous, as well as more points cost.

To be honest, the modern mantra of ‘game balance’ wasn’t something that loomed large in our approach to games design. We were more interested in creating games that were exciting and engaging than in games that were perfectly balanced. Obviously, there has to be a degree of parity between forces, and we aimed for that. We weren’t creating games for hardened rules-lawyers or competition led players. We were creating games for enthusiastic youngsters and cheery adults who enjoyed pushing toy soldiers around and rolling dice over a few beers.

Now for a curiosity from my home country: a WFB partwork was released by Altaya in Spain in 2000. As I understand, this was a job designed by the GW studio in Barcelona. Were you aware of this product and did you participate in it in any way? This product was a success in Spain and very popular with young people because you could buy it at street kiosks. (You can see pictures of the collection here: https://cargad.com/index.php/2013/10/29/warhammer-el-coleccionable-de-altaya/)

RP: Yes, there was time when we undertook part-works projects in Spain and elsewhere. I remember it all happening, and the studio would have supported those projects by providing artwork, photos and sometimes text. By that time, I’d moved on from the studio and my role was restricted as part of the executive. I still managed to undertake a few games design projects to keep my hand in – not least The Lord of the Rings Strategy Battle Game – but the product line wasn’t my ‘job’ anymore.

I think when we found out how popular part-works were in Europe, we just pushed at that open door. Later on, we would do part-works for The Lord of the Rings, and that really led to a huge growth in sales almost overnight. But that… as they say is another story.

Looking back, is there a particular rule or game mechanic from Warhammer Fantasy Battle or Warhammer 40,000 that you would have changed or simplified? Conversely, what decision related to the design of those two games are you most proud of?

RP: I can’t think of anything in particular. The rules of the game were just something I contributed to the project. From the 90s, I’d be more actively engaged in working out the tooling, getting the artwork underway, and making sure the models were ready in time. Compared to all that, designing the games was relatively easy! I did enjoy doing the games design, as well as the background writing and world building: it was the fun part of the project.

One thing I did come to regret was the card-based magic system for 4th and 5th edition. The reason is nothing to do with the game design, it’s to do with the way the company changed in the early 90s. The card magic system was conceived and designed when we were exclusively an English language company. Hence, I worked out the costings for the cards based on what we thought we could sell, and similarly for the card inserts. What I didn’t know, was that within a few years we would be producing the same products in French, Spanish, German and Italian. All of these were much smaller markets, so the cost of printing the Battle Magic supplement, with its cards and card insert content, was crippling – especially for the smallest market. Which was Italy. I think whenever we had to reprint Battle Magic in Italian, we basically lost money on every one we sold! That’s why we ditched the card-based magic system for 6th edition.

Design Philosophy and Other Projects

How much did the availability of miniatures from Citadel influence your design work on a new game or expansion? Did you ever feel internal pressure to create rules tailored to specific miniatures that Citadel was keen to sell at the time?

RP: Warhammer was always a means of marketing the models, and the models drove most aspects of the rules design. Throughout the 80s the games writers’ job was to write rules for the miniatures as well as the other promotional material, box backs, bits of fiction, whatever was needed at the time. The models, rules and artwork were all developed together within the studio, so – depending upon the time frame – the creative staff worked together on these things. Often the model makers had ideas for rules or background details, sometimes the game designers had an idea for a model, or an artist would render something that would make a great model or basis for a character piece. We worked together on these things.

There were periods when the company was growing and it became necessary to introduce some management into the process, notably in the mid to late 80s. As a result of that the writers became isolated from the model making, artists, and production to some extent. I recall that a model would often get plonked on your desk with an instruction to write rules for whatever it happened to be. Often, it was a case of coming up with something for the monthly White Dwarf deadline. If you were unlucky, that could be ‘by 5 o’clock’! When I took over the studio in the 90s, we worked in a far more communal and organic fashion, mostly because I was driving the product line and I was in the office, within arm’s reach of what was going on.

To what extent did player feedback influence the evolution and development of games like Warhammer Fantasy Battle and Warhammer 40,000?

RP: We didn’t really get much player feedback in those days, and what we did get was not always all that useful. We mostly played the games and compared notes, and sometimes non-studio staff would join in. The retail guys would sometimes point things out or ask questions. Our mail order people were set-up to answer queries by post. Mostly, they could answer the questions themselves, but otherwise they would send the letters on to us and we would provide answers. We learned a few things that way, especially rule loop-holes that we’d missed or cunning ploys players had come up with to abuse some aspect of the text. If we’d miscalculated or missed some ‘winning ploy’ – often involving a magic item or some hurriedly developed special rule - we did take notice and tried to offer corrections or interpretations as opportunity permitted.

I'd like to ask for your thoughts on the 'Oldhammer' movement. With Warhammer: The Old World bringing back older editions and even re-releasing classic metal Citadel miniatures, what is your perspective on this enduring appreciation for the early years of Games Workshop?

RP: Yes, there is an annual Oldhammer event held at Wargames Foundry, which I try and get to. It’s turned into a bit of a GW old boys (and girls) re-union. I’m very pleased to know that folks are still interested in the old games, and continue to remember our efforts fondly after all this time. GW is a very different and much bigger company nowadays, of course, although I’d like to think I did my bit to make it so!

Regarding the Terror of the Lichemaster mini-campaign for WFB that you designed in 1986, could you tell us about your objectives in combining a narrative history with a structured campaign for players?

RP: That was just how the teenage Richard Halliwell and I played fantasy games in the late 70s. Partly we were inspired by the Old West Skirmish rules by Colwill, Curtis and Blake, now reprinted as part of John Curry’s History of Wargaming project. That game had elements of role-playing and narrative continuity before D&D existed. There was a previous narrative campaign for Warhammer called Bloodbath at Orcs Drift, by Gary Chalk and Joe Dever, which was very popular, and great fun. I took the basic structure developed by Gary and Joe, and used it for my own Lichemaster story.

The basic structure is what I call a ladder campaign – in that you progress rung by rung from the bottom to the top. The results of each game will influence the set-up, forces, or other circumstances for the next, but ultimately, it’s about working your way along to a final ‘do or die’ climax. It’s a nice format because it’s essentially a story that plays out as a series of wargames, with all the opportunities for creating interesting situations and characters that you’d find in fiction.

In 1990, you co-authored the Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay campaign Lichemaster with Carl Sargent. This publication included a section for adapting battles to the tabletop using Warhammer Fantasy Battle rules. What was your involvement in this project and the integration of the two systems?

RP: I honestly don’t remember having anything to do with that at all. It could be that my name was added simply because Carl borrowed from my original story. Carl was a lovely chap, very sharp and funny, but we didn’t work on the same things. I was really devoted to Warhammer and the tabletop games. Carl was very much a role-play author – and a damned good one!

In Vengeance of the Lichemaster, the inclusion of a character named Mikael Jacsen, a clear reference to Michael Jackson's 'Thriller,' is a notable example of the kind of humorous 'Easter eggs' found in GW's work. We were hoping you might share some anecdotes about this internal practice at GW, or perhaps mention some of the other 'funny names' you were responsible for?

RP: Yes, in those very early days we didn’t take ourselves too seriously, and we’d often invent silly names or sneak in references to people we worked with. Tony Ackland and I had fun coming up with all the names for the original Slann, which are all pseudo-Aztec names, but usually involve some terrible pun or word-play. One of Tony’s best was – if memory serves – Gynzmytipl – i.e ‘Gin’s my tipple’. Richard Halliwell came up with the revolutionary Dwarf miner Arka Zargul – which is a pun on Arthur Scargill – the leader of the miner’s union who plagued British governments throughout the 1970s.

Moving into historical wargaming, how did the idea for Warhammer Ancient Battles come about? What do you believe were its key differentiators from other historical wargames of that period?

RP: Well, I’ve always been fascinated by ancient history and ancient wargaming, and from my early teenage years I collected and fought with ancient armies. Ancient period wargaming and fantasy battle style wargaming are essentially the same thing – with the addition of monsters and magic – but mechanically you have ancient or mediaeval style armies in both cases.

I think what happened was we got hold of a copy of Tactica by Arty Conliffe. This was an American ruleset, produced to what was then a very high standard with colour throughout, photographs of models, diagrams, and all nicely explained. In other words, following much the same design ethic as Warhammer itself, and quite unlike the general standard or approach of traditional historical wargames rules.

The rules looked interesting, so Jervis Johnson and I decided to play a few games. I buffed up my old Romans and Seleucids and got two forces together to meet the rather exacting requirements for the game. After a few games we decided that the game was interesting, but a bit limited tactically, and not very accessible for new players because the armies were all of a fixed size and composition as well as rather large. We felt that, although the game was nicely presented and mechanically pleasing, the fact that you needed a vast army to start with, and that the army compositions were fixed – i.e. no choice of units at all – was way too restrictive.

I don’t recall which of us said it – but having played a good few games we both came to the conclusion that we could produce a much more interesting game using the then new Warhammer 4th edition as a basis. We just took our existing Warhammer text and re-worked it, involved a few more old ancient players in the project, got folks in the studio to help out after work as a favour, and generally pulled the whole thing together out of hours. At the time the Perrys were making ancient ranges for Wargames Foundry, and we played a lot of initial games round at Alan Perry’s house.

Ancient wargaming at the time was in a fairly moribund state, with mostly older players fighting competition style games using their – usually old – 15mm armies and the current Wargames Research Group rules. That was quite a large player group, having mostly grown up in the 70s at the same time as folks like myself and Richard Halliwell and Jervis Johnson, but by then commercially irrelevant. Very few players were invested in collecting modern, 25mm/28mm armies, so Warhammer Ancients did a lot to revitalize ancient wargames and introduce new players.

Warhammer Historical Wargames was always something of a side-show, and although it grew and eventually acquired a manager within the GW business, it was always an indulgence and never commercially significant for the company. Ironically, had it been an independent company it would certainly have been one of the largest and most profitable historical wargames publishers. So it goes.

Reflecting on the Hobby

Looking at the wargames industry today, do you believe the creative spirit of game designers is still thriving, or do you think the commercial and economic aspects of the business have become too influential?

RP: I don’t know enough about the contemporary wargames industry to answer that. I always wanted to make a living for myself and for others, doing something I enjoyed, and which was never regarded as a ‘proper job’ at the time. The idea of making a living out of designing wargames in the 70s was absurd. People who designed games did so as a hobby and generally speaking had ‘proper’ jobs too.

So, the idea that we were motivated by a ‘creative spirit’ misses the mark somewhat. We wanted to make a living and were alive to the commercial and economic realities of what we were doing. Creating games was just what some of us did, and not necessarily as our ‘job’ either. I joined Citadel Miniatures to do the mail order, packing and dispatching customers orders, helping out with trade orders when required, learning to cast, making moulds, attending shows with the trade stand, and pitching in with whatever else needed doing.

It wasn’t until the company had grown much bigger that I was able to write full-time, and even then, it wasn’t until later still that we started to design games within work time. To give you an idea of that, I wrote the entire first manuscript for Warhammer 40,000 freelance, not during work hours, and that was in 1987. The creative spirit was alive and well… but not necessarily 9 to 5.

To conclude, are you still in touch with any of your old colleagues from the early days of GW? Do you ever get together to play with Jervis Johnson, Phil Gallagher, or Andy Jones? The fans would be thrilled to know.

RP: I remain good friends with the Perry’s as well as my old comrade John Stallard, who ran the sales side of GW when I was running the product side. John started and is the principal owner of Warlord Games, of which I am also a small part, and have contributed various rulesets including Black Powder and Hail Caesar.

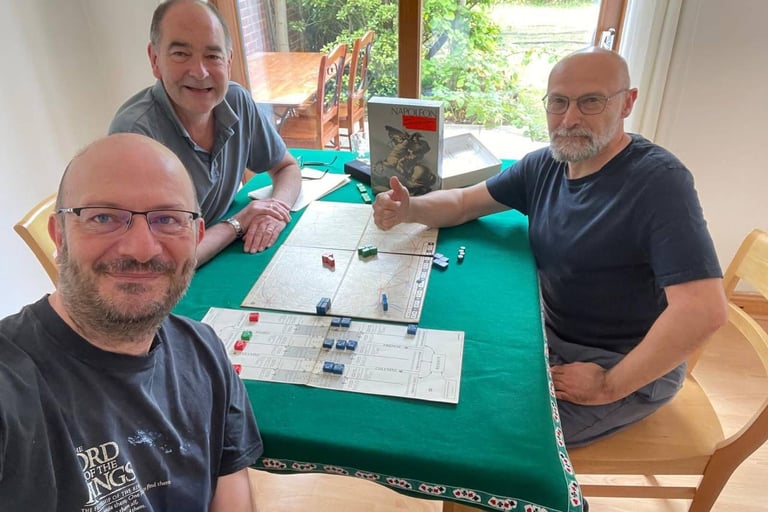

I meet up with Jervis and Alessio Cavatore to play board games, and we help each other out with projects on occasion. I have a good-sized wargames table and separate games room, so I sometimes host games as they are developed or tested. Local games often involve Aly Morrison and Dave Andrews, both of whom still work at GW, although they are primarily historical wargamers. Nigel Stillman and I meet up every so often for a game – Nigel is always working on some wargames project or other!

Andy Jones, I meet up with occasionally and mostly for a curry. He has taken himself off into the wilds of Lincolnshire! Andy wasn’t really a historical gamer like the rest of us – and I think that’s what kept our ‘crowd’ together – meeting up to play games, at local shows, or to support various magazine projects for Wargames Illustrated (based in Nottingham) or Wargames, Soldiers and Strategy magazine. Always good to meet up with Andy though 😊

Phil, I’ve not seen for many years. He was part of the ex-TSR role-play team that included Jim Bambra, Mike Brunton and -by association – Graeme Davis. Phil was one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. He re-trained within GW for a role as our licensing executive, and subsequently left GW and moved to the USA where I believe he works in academia. He was also a keen and talented amateur actor – and may still be for all I know!

Thank you so much for your time, Rick. It's been a real pleasure talking with you, and your insights have given us a fantastic look into the history of the hobby we all love. It's clear that your work has left an incredible legacy, and we're so grateful for all the games that you have developed until today.